- Ukraine’s Western allies have promised to send it more long-range missiles.

- Kyiv has already demonstrated it can use ATACMS and Storm Shadows to hit high-value Russian targets.

- Former US military officers say more of these missiles will expose Russia on the battlefield.

NATO countries are outfitting Ukraine with additional long-range precision missiles that have already been used by the country to strike Russian airfields, naval headquarters, bridges, and other high-value targets.

These Western-provided missiles give Ukraine’s deep-strike capability a major firepower boost. Former US military officers told Business Insider that the munitions could help Kyiv go after locations that are essential to Russia’s operations, and leave its combat and support forces with “nowhere to hide.”

Ukraine is facing Russian offensives that may get more intense going into the summer, but these weapons could help hamstring Moscow’s efforts.

“If you’re worried about Russian forces overrunning your defenses, you want to go after the headquarters and you want to go after the logistics that would enable Russian attacks,” said Ben Hodges, a retired lieutenant general and former commander of US Army Europe.

White Sands Missile Range/John Hamilton

The US last month acknowledged that it had secretly shipped Ukraine a number of MGM-140 Army Tactical Missile Systems, also known as ATACMS — earlier this spring as part of a $300 million weapons package it announced in March. The number of missiles isn’t publicly known, but ATACMS missiles average about $1.3 million each.

Jake Sullivan, the Biden administration’s national security advisor, said in late April that the US would send Ukraine more ATACMS after passing a $61 billion aid package that spent months held up by Republicans in Congress. The legislation required that Washington transfer the munitions.

ATACMS are tactical ballistic missiles that come in several variants. Ukraine previously received ones that have a range of 100 miles and can disperse nearly 1,000 submunitions over a large area, making them particularly damaging to airfields. Last fall, Kyiv used the missiles for that exact purpose.

The US also has ATACMS that can travel up to 190 miles; one variant has a unitary warhead, while the other can scatter some 300 submunitions. Ukraine has long pressed Washington for these extended-range missiles, though it’s unclear what Kyiv has actually obtained.

General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces/Screengrab via X

Around the same time, in late April, the UK announced it would send Ukraine additional Storm Shadow cruise missiles as part of the country’s largest-ever weapons package (£500 million, or $633 million), which included over 1,600 strike and air-defense munitions.

Days later, Britain’s defense minister Grant Shapps disclosed for the first time that Italy had, at some point, also supplied Kyiv with Storm Shadow cruise missiles (France has sent Kyiv its own version of the munition called SCALP-EG).

These air-dropped missiles can fly at low altitudes to avoid detection and have been used to strike Russian naval headquarters and vehicle-repair depots in the occupied Crimean peninsula. Their 155-mile range puts them in between the ATACMS variants.

It’s unclear exactly how many ATACMS and Storm Shadow missiles have already arrived in Ukraine this spring, nor is it known how many more the country can expect to receive in the coming weeks as it tries to stall Russia’s momentum on the ground. Kyiv previously obtained a limited number of both munitions from the US and its European allies.

Ben Stansall/AFP Photo via Getty Images

A larger arsenal of missiles could strip Russia of its ability to stage crucial assets within 100 miles of the front lines, said Dan Rice, a former US Army artillery officer who previously served as a special advisor to Ukrainian military leadership. “That puts tremendous pressure on all of their key high-value targets.”

“You have a 600-mile front and then you’ve got a hundred miles deep — where do you hide everything?” said Rice, a longtime advocate for sending cluster munitions to Ukraine and now the president of American University Kyiv. “Your transportation nodes, your railway stations, your supply depots, command and control — most importantly, your anti-aircraft systems.”

Ukraine’s battlefield reach has steadily grown throughout the full-scale war. What started out with short-range artillery improved over time with the arrival of US-provided High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems, or HIMARS. These game-changing weapons suddenly put Russian logistics centers, ammunition dumps, and command and control nodes within firing range.

Russia adapted to the HIMARS by moving its critical assets out of reach and jamming the munitions. The arrival of Storm Shadow missiles — and, several months later, ATAMCS — presented new challenges for Moscow, but Ukraine has received so few it has had to bee choosy over what to target.

Serhii Mykhalchuk/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Hodges and Rice say a larger arsenal of ATACMS and Storm Shadows can give Ukraine both the reach and inventory to smash the high-value targets that sustain Moscow’s war efforts like supply depots and maintenance facilities. Indeed, Kyiv has used the American missiles in recent weeks to strike Russian airfields and troop gatherings.

“When you start taking those off the board, then it doesn’t matter how much untrained, mass infantry — cannon fodder — that the Russians have,” Hodges said. “I think long-range precision strike is becoming the dominant factor on the battlefield.”

Missiles like ATACMS and Storm Shadow “will enable Ukraine to neutralize Russia’s advantages and eventually enable them to regain the initiative,” he added. Ukraine has also long sought Germany’s Taurus missile, whose range is more than a 100 miles farther than ATACMS, but Berlin has so far declined to provide them.

The increased arsenal comes at a critical point. Russia is making gains on the battlefield as its bigger war industry shifts to mass-producing the drones and glide bombs that are pounding Ukraine’s defenses.

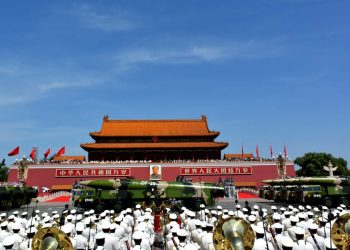

Russian Defense Ministry/Handout/Anadolu via Getty Images

Ultimately, however, the effectiveness of Kyiv’s long-range strike regime depends on how many munitions it receives — and how it uses them. Ukraine had long been restricted to using ATACMS and Storm Shadow missiles only inside occupied territory, although the UK recently agreed to let Kyiv use its weapons to strike inside Russia.

Whether or not the US follows suit remains to be seen. Analysts and officials have said that US restrictions went on to prevent Ukraine from putting up an effective defense and have essentially allowed Russia to conduct a new assault in the northeastern Kharkiv region.

The advances appear to be the start of Moscow’s anticipated summer offensive, as Ukrainian forces are increasingly stretched out across the front, Jack Watling, a senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute think tank, warned in an analysis this week.

“The outlook in Ukraine is bleak,” Watling said. “However, if Ukraine’s allies engage now to replenish Ukrainian munitions stockpiles, help to establish a robust training pipeline, and make the industrial investments to sustain the effort, then Russia’s summer offensive can be blunted, and Ukraine will receive the breathing space it needs to regain the initiative.”