Mehdi Maloof, Tarbooze, and more strip music to the bone

As golden hour settled over Karachi on Sunday, a soft current of sound threaded through a patch of trees in Clifton. It wasn’t the distant echo of city noise or the heavy pulse of a commercial concert. It was gentler, human-sized — voices, strings, the occasional foot tap on dry leaves. In the heart of The Urban Forest, a rare oasis in an overstimulated city, Forest Jam was underway.

Organised and conceived by indie wife-husband duo Tarbooze, consisting of Wishaal Khalid and Danial Shahid, Forest Jam was part gig, part gathering, part reclamation. The lineup — Tarbooze, Zarf, Asaduu, Dulhay Mian, and Mehdi Maloof – spanned moods and cities, from Karachi’s alt-rock echoes to Quetta’s bedroom pop and an unputdownable melancholia that far exceeds spatial confines. But beyond the music, it was also a way of holding space for the kind of listening, feeling, and communion that rarely finds room in the algorithmic grind of modern music culture. In an industry increasingly shaped by corporate sponsorships and polished “experiences,” Forest Jam was refreshingly DIY, vulnerable, and intimate.

Rooted in community

Tarbooze opened the night with a reverent rendition of Zeb & Haniya’s Rona Chor Diya, the song’s rhythmic optimism riding the soft breeze and setting the tone for what would be an evening of emotional transparency. “Haniya was a mentor,” Wishaal told The Express Tribune. “I hadn’t known her for long, but she really encouraged me when she heard I was into music production. I grew up on her music and her loss felt personal.”

They followed with their own Toofan, a song that subverts its title’s stormy implications. Introspective and sombre, it invited the audience into a quiet space of contemplation. “Music is one of our primary ways of emotional regulation and expression,” Tarbooze explained. “It connects us to our reason for being alive.”

But Tarbooze weren’t just the opening act. They were the reason the event existed at all.

“We used to rely on other venues and entities inviting us to perform in order to sing for an audience. But indie musicians in Pakistan don’t often get opportunities to perform their music,” said Danial. “We have a small but dedicated listener base that won’t be selling out large venues like pop musicians. So instead of waiting for someone to invite us, we decided to take ownership and organise the performance ourselves.”

That ownership has meant embracing the messy, beautiful work of building a community. “What made the first jam session special,” Wishaal mused, “was that it wasn’t dependent on a middleman like the venue or the sound walas – who often limit the artist’s influence. This was a community-run event.

Tarbooze’s approach to audience-building is unconventional, but purposeful. “A lot of indie musicians I know aren’t looking to make profits. They just want to be heard,” the duo expressed. “The world might not be ready to hear what we have to say, but maybe the task is to make the music, send it out into the world, and step away.”

No holds barred

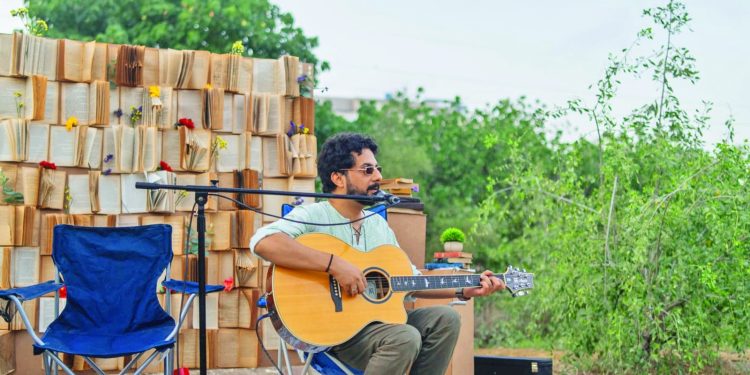

The gig’s visual identity also spoke to this layered ethos. Behind the performers stood a textured mosaic of open books – spines broken, pages splayed, a few ribbons, flowers, and ferns strung between volumes. Artist Maham Peerzada, who is also Mehdi’s wife, created the piece. “It wasn’t part of the original plan,” Wishaal shared. “But Maham offered to help, and it completely changed the vibe. I think I’m going to try to get her on every show!”

The second act, Zarf, shifted the atmosphere. Composed of Farrukh Zaidi on vocals and Mubashir Taimoor on guitar (with bassist Mudassir Zaki absent), the alt-rock band began their set with Saazish, a fan favourite that bridges sentiment and movement. It’s a song that never settles, hovering between melancholic introspection and a driving, rhythmic insistence. Live, it felt both raw and refined. Zarf didn’t need spectacle. Their strength lay in texture: layered guitar, gentle vocals, the kind of sonic space where silence is as integral as sound.

Then came Asaduu, an emerging artist from Quetta based in Karachi whose playful, expletive-anchored Ch*tiya chronicled the dissolution of a toxic friendship. It was self-deprecating, catchy, and sharply relatable. But beyond the humour, Asaduu’s presence felt quietly radical – a reminder of how fragmented the country’s music scenes remain, and how much promise lies in cross-city, cross-genre collaborations.

Political bite

As dusk deepened and the air cooled, Nadir Shahzad took the floor under a new name: Dulhay Mian. The former frontman of Sikandar Ka Mandar has long been a fixture of Pakistan’s indie scene, known for his lyrical candor and socio-political bite. His new act carried those same signatures, but with a sharper edge. Khalil Sahab, with its innuendo-laced lyrics, felt like watching a sharp comedy sketch slowly morph into political theatre. “My inspiration was Father John Misty,” he said. “He says serious things in a comedic style. I want to create a similar effect – but keep it Pakistani.”

American Dollar Exchange Rate

American Dollar Exchange Rate