How it became woke to love King Khan but no one knows why

In one of the most iconic scenes from Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Shah Rukh Khan teeters on the edge of every woman’s worst nightmare. His character, Raj, finds himself locked in a train compartment with Simran (Kajol). Simran is reserved, traditional, and decidedly uninterested in the charming yet invasive stranger determined to disrupt her solitude.

She doesn’t lash out immediately. When Raj awkwardly jokes, “There’s no one at home,” after knocking futilely on the compartment door, Simran offers a polite smile and turns her attention back to her book. But Raj, like so many men before him, doesn’t misread the signalshe blatantly ignores them. What follows is an escalating series of humiliations: Raj flaunts her lingerie with a smirk, croons “Tum mein, ek dabbe mein band hoon,” slides on his sunglasses, and cosies up beside her. When Simran firmly says, “Please leave me alone,” Raj doesn’t just dismiss her resistance; he mocks it, resting his head brazenly on her lap.

If Simran had been asked whether she’d rather share that compartment with a man or a bear, the answer would’ve been obvious. Yet, DDLJ endures as a timeless love storya cornerstone of Bollywood’s romantic canon.

It also serves as the prototype for Shah Rukh’s signature brand of on-screen masculinity: one that smooths over boundary-pushing behaviour with irresistible charm, blurring lines between flirtation and coercion. This archetype, rooted in working-class, old-school romance, isn’t just central to Shah Rukh’s personait has informed and sustained Bollywood’s storytelling for decades, proving both durable and lucrative.

A strange legacy

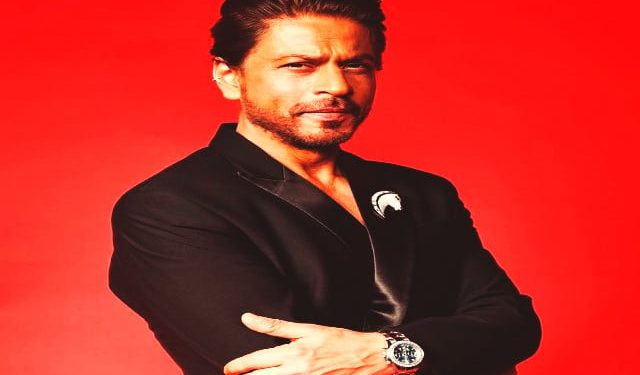

2023 marked Shah Rukh’s roaring comeback, a year that saw him dominate box offices with Pathaan and Jawan, cementing his position as Bollywood’s reigning superstar. His return wasn’t just cinematic; it was cultural, sparking renewed adoration from fans and a frenzy of discourse around his legacy.

In 2024, Shah Rukh redefined what cinematic stardom could mean – and demand – in a globalised, hyper-connected era of Indian cinema. At the 24th International Indian Film Academy (IIFA) Awards, his performance in Jawan earned him the Best Actor award. Later in the year, under the starry skies of Switzerland, he became the first Indian artist to receive the Pardo alla Carriera Ascona-Locarno Tourism award at the 77th Locarno Film Festival. Meanwhile, the internet anointed him as a feminist icon, a title buoyed by his comments on gender equality and carefully curated gestures of respect for women.

Two years before DDLJ, Shah Rukh was a new and promising villain. His portrayal of Rahul Mehra in Darr (1993) was sinister and obsessive, defined by the chilling refrain, “Tu haan kar ya na kar, tu hai meri Kiran.” In both Darr and Baazigar, Shah Rukh embodied a menacing intensity, earning acclaim as a popular antihero. But these films barely hinted at the softer, insistent romantic persona that would later crown him as King Khan.

The Shah Rukh Khan adored by women didn’t always come with rippling six-packs, veiny biceps, or shirtless displays under waterfallsthat remains Salman Khan’s territory. Instead, Shah Rukh’s charm has always been rooted in his boyish charisma and razor-sharp wit. As an actor, his performances are solid, though often eclipsed by his larger-than-life stardom. He is, and has always been, the nation’s undefeated sweetheart. And make no mistakehe adores women.

Off-screen, Shah Rukh isn’t far removed from his on-screen persona. Sure, he will not be losing his shirt to reveal a sculpted chest – that is still Salman Khan’s expertise – but he reveres women. Call it SRK feminism. “How have you bewitched women all over the world?” a woman asked him at a public event. “I have lots of free time. Every time I see a girl, I go there ,” Shah Rukh quips with a laugh before adding in a serious tone, “For women, love means respect, and I respect every woman. That’s why they love me so much.”

Finding an escape

There was a time when Shah Rukh was subject to uncritical adoration. Loving him, enjoying Bollywood, or even supporting artists deemed “problematic” post-cancellation was relegated to the realm of guilty pleasures. In the immediate aftermath of #MeToo, the pressure was palpable: to curate a catalogue of offences, however minor or major, and to refrain from indulgenceat least without first issuing a disclaimer of disapproval.

Years after #MeToo, that pressure has metamorphosed into personal manifestos that must account for all that is consumed. It may not be enough to love Shah Rukh and not know what his legacy means for women.

But where Shah Rukh’s romanticised masculinity fits within feminist discourse wasn’t always at the forefront. It takes either selective amnesia or being born into a later generation to forget the swirling rumours of his alleged affair with Priyanka Chopra or how his on-screen avatars inspired countless men to chase women who had clearly said no. Shah Rukh was always loved but not always praised.

A woman’s man