We don’t care if these pioneers borrowed from everyone in the ’80s

If you are looking for the quintessential Pakistani boyband, you could do a lot worse than Vital Signs. Obligatory gaggle of eye-candy hotshots? Check. Music videos with interesting close-ups and the wispiest of links to their lyrics? Check. A musical catalogue that enveloped a whole nation? Check, check, a thousand checks.

To belong to a boyband is a brave career choice, due to the simple fact that whichever fan swears allegiance to one is automatically branded ‘unrefined’. Still, it is that very all-encompassing relatability of boybands that makes them both adored and reviled in equal measure, whether they hail from the techno-fuelled twenty-first century or the synthesiser-worshipping ’80s. To openly admit your playlist is littered with boyband hits leaves you unworthy of basking in the company of music fans with more eclectic needs. (You can call us snobs. We don’t mind.)

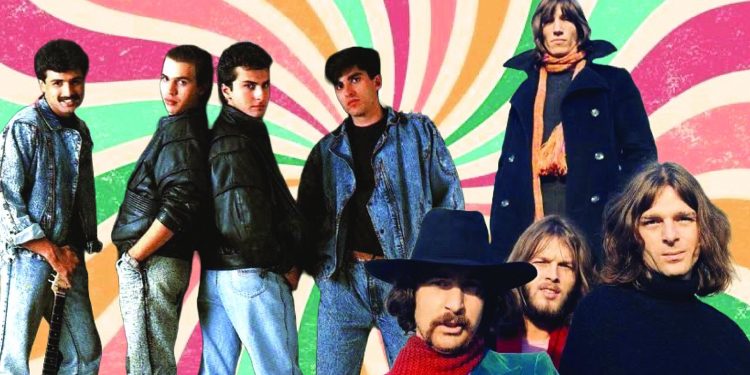

But to talk trash about Vital Signs, the OG Pakistani boyband, is to play a traitorous game. The pulse of a generation of music fans beat in time to whatever Vital Signs spewed out, despite – or perhaps because of – their unapologetic inspiration from their Western cohorts. To embrace Vital Signs is to love Pink Floyd, The Police, UB40, and even that ’80s stalwart Bryan Adams. Painstakingly paving the way so that Strings could run, Junoon could fly, and so the next generation of bands could continue to be inspired via Rohail Hyatt’s Coke Studio, Vital Signs were the pioneers of accessible music in Pakistan. They brought with them not just instant recognition with lyrics that roll off the tongue, but songs flavoured with the wealth of styles brewing beyond Pakistani shores. Paired with Junaid Jamshed’s soft unassuming vocals, here was a group that allowed you to believe that you, too, could sing if you truly wanted to.

A touch of Floyd

If you loved the pensive Ajnabi or the electronic whimsical opening of the melancholic Janaan Janaan – the first few bars of which bear seemingly little relation to the opening verse and everything else that follows – then it is likely you would also hold a burning flame for the syncopated opening rhythm of Pink Floyd’s Money. Or if the sound of pinging cash registers, syncopated or otherwise, is not your thing, the two-second sliding synth 48 seconds into Janaan Janaan will whisper a tantalising hint of Floyd’s epic Comfortably Numb. After all, to hold a candle for Vital Signs is to pay homage to the ’80s – and no musical snob’s collection would be complete without a hearty dose of the psychedelic Pink Floyd. Or at the very least, Comfortably Numb.

“More than any of the other band members, Rohail Hyatt was inspired by Floyd,” says musician and vocalist Abbas Ali Khan in conversation with The Express Tribune. “We also that inspiration in how he later went about with Coke Studio. He made the songs in different phases, and that free-flowing sound was there.”

Does the Vital Signs legacy deserve to be tarnished with accusations of plagiarism? Heaven forbid. To seek inspiration is one thing; to shamelessly copy is another. Despite scathing YouTube videos that show a side-by-side comparison of Vital Signs tracks juxtaposed with similar-sounding artists of that era, it is safe to say that they avoided the shamelessly copying route – certainly when it comes to Floyd.

“I think there are two elements of the potential of Floydian influence on Vital Signs; the first is on songwriting, and the second is the production and recording process,” commentator Fasi Zaka tells The Express Tribune. “I think Vital Signs did make some serious and brooding music – but I wouldn’t call it Floydian. But in terms of production, I do think the third album, Hum Tum has that bent.”

Borrowing from the ’80s

Sharing a ‘bent’ is an affliction that plagues all musicians from all eras, although it is extremely handy for anyone wanting to accurately date a piece of music to within a decade. The Beatles may have immortalised their contribution to music with their originality, but even their early tracks – Love Me Do, for example – leaned heavily on the rock ‘n rollers of the late fifties, such as Chuck Berry. Meanwhile, marching further ahead in time, unless you were a teenage girl in the nineties, you would need the skills of Sherlock Holmes to isolate any differences between Backstreet Boys and ‘N Sync. All works of music are linked – some just more so than others.

When it comes to Vital Signs, Zaka offers a succinct explanation about where their inspiration stemmed from. “We can look at it from two lenses,” he observes. “The first is who they accepted as influences. The second is what shows up in their music. They loved a lot of progressive rock bands, some of whom were popular and respected. Bands they liked – like A-ha and The Police – do show up in influences in the music for the late ’80s pop sound.”

Like other Vital Signs fans, Khan tends to agree. “I think Junaid was more inspired by A-ha, and his vocal tone was very similar,” he notes.

That signature synth-laden late ’80s pop sound has much to answer for. It is a sound our pioneering pop heroes embodied with reckless abandon, bleeding into the veins of their fans and conjuring up whatever emotion they pleased. If your tastes veer towards the jaunty, you can hardly fail to be charmed by the UB40-inspired Samjhana (think Red Red Wine). Or, indeed, the sunshiny Woh Kaun Thi, which brings back irresistible echoes of Adams’ Can’t Stop This Thing We Started with its chord progression and hollow electronic drums.

But if you prefer your music to be tinged with melancholy, Tum Mil Gaye will cast its spell over you – as will its musical twin and forerunner, Alan Parsons’ fuller-bodied Eye In The Sky. Both tracks are set in the beautifully haunting key of B-minor (relatively easy for any guitar player to adhere to thanks to being a barre chord) and both songs also follow a near identical structure and lyrical cadence.

Regardless of these faithful regurgitations of existing works, it would be unkind to judge Vital Signs too harshly. Thanks to their keen understanding of Western pop, these men were the trailblazers who incorporated an element of foreign coolness into Pakistani music. Even if they had never spat another track, the mere existence of their trump card Dil Dil Pakistan has sealed their legacy. To be the voice of the anthem that heals cricket-induced sorrows is enough to cement their place in music history. If there is one thing we Pakistanis need more than anything, it is an antidote to cricket woes. And for that, we can forgive a little borrowing from the ’80s.