Intermittent fasting (IF) has become the all rage — done by many to burn fat and stay fit, while others do it to get a clearer mind and detox their bodies. Some of its proud adherents include: Nicole Kidman, Jennifer Aniston, Halle Berry, Scarlett Johansson, Reese Witherspoon, Hugh Jackman, and billionaires like Elon Musk and Jack Dorsey.

Beyond the fad, however, no human trial has looked into the benefits of IF, specifically in helping push diabetes into “remission” (cancellation, reversal).

Until now.

A new randomised, albeit small, trial on IF did just that: it was conducted on 72 Type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients. The research has kicked up excitement in the medical fraternity, as well as a healthy dose of cynicism.

Why is it significant?

It’s a pioneering clinical trial involving Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) patients who undergo intermittent fasting (IF) as “treatment” (instead of medication) which shows — for the first time — how it eventually leads to weight loss, and “remission” of the disease.

The study, titled “Effect of an Intermittent Calorie-restricted Diet on Type 2 Diabetes Remission: A Randomized Controlled Trial” came out December 14, 2022 in the prestigious Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM), published by Oxford.

What are the trial results?

In a nutshell, it showed a high percentage of T2D trial patients who experienced remission of the disease, compared to a “control” group. The initial rate of remission was 47 per cent in the treatment group (those who practised IF) and 2.8 per cent in the “control” group (non-IF).

Moreover, the treatment group lost about 9 per cent of their starting body weight; there was no reduction for the “control” side.

CONTROL GROUP VS TREATMENT GROUP

In a scientific investigation, a control group is used to establish causality — by isolating the effect of an independent variable (i.e. effect of intermittent fasting on diabetes remission on the treatment group).

Researchers may change the independent variable in the treatment group and keep it constant in the control group. Then they compare the results between the two groups.

In the scientific community, however, there’s a popular adages that goes: “Correlation does not imply causation,” i.e. the higher number of remission in the treatment group does not mean the IF regimen was the direct cause.

What are key numbers involved in the trial?

The trial on 72 patients — all confirmed T2D patients — was randomised in which there were 36 volunteers assigned to the IF group; the same number was assigned to a control (non-IF) group.

There was a 3-month intervention (when IF was practiced by the treatment group). There was follow-up for three months to assess initial rates of diabetes remission. And, to assess the durability of that remission, a follow-up came at one year (12 months).

The researchers initially screened 246 patients for the trial, and whittled it down to 72 who met their trial criteria.

How was “remission” defined in the trial?

The study defined remission level as: HbA1c (long term blood sugar level) of 6.5 per cent or less — at least three months after discontinuing diabetes medications.

Is this enough to prove IF works to help T2D patients go into remission?

No.

Due to the study’s small size, it does not mean that the 36 people who responded well to IF can be generalised to a much bigger population. And IF may not work for all diabetes patients.

What is the significance of the study?

The study is significant as it’s the first human trial to show an association between IF and T2D remission.

Given the small trial size, however, to conclude that this approach will be broadly effective in the population of people with type 2 diabetes (about 422 million people globally) cannot be made.

Diabetes cases

• 422 million: number of people worldwide who have diabetes — 1 in every 11 of the world’s adult population, as per WHO estimates.

• 46%: percentage of people with diabetes that are undiagnosed.

• 1.5 million: number of deaths are directly attributed to diabetes

• 642 million: Number of people living with diabetes worldwide by 2040 (WHO projections)

• 80%: Percentage of US population that have insulin resistance, a condition that eventually leads to diabetes.

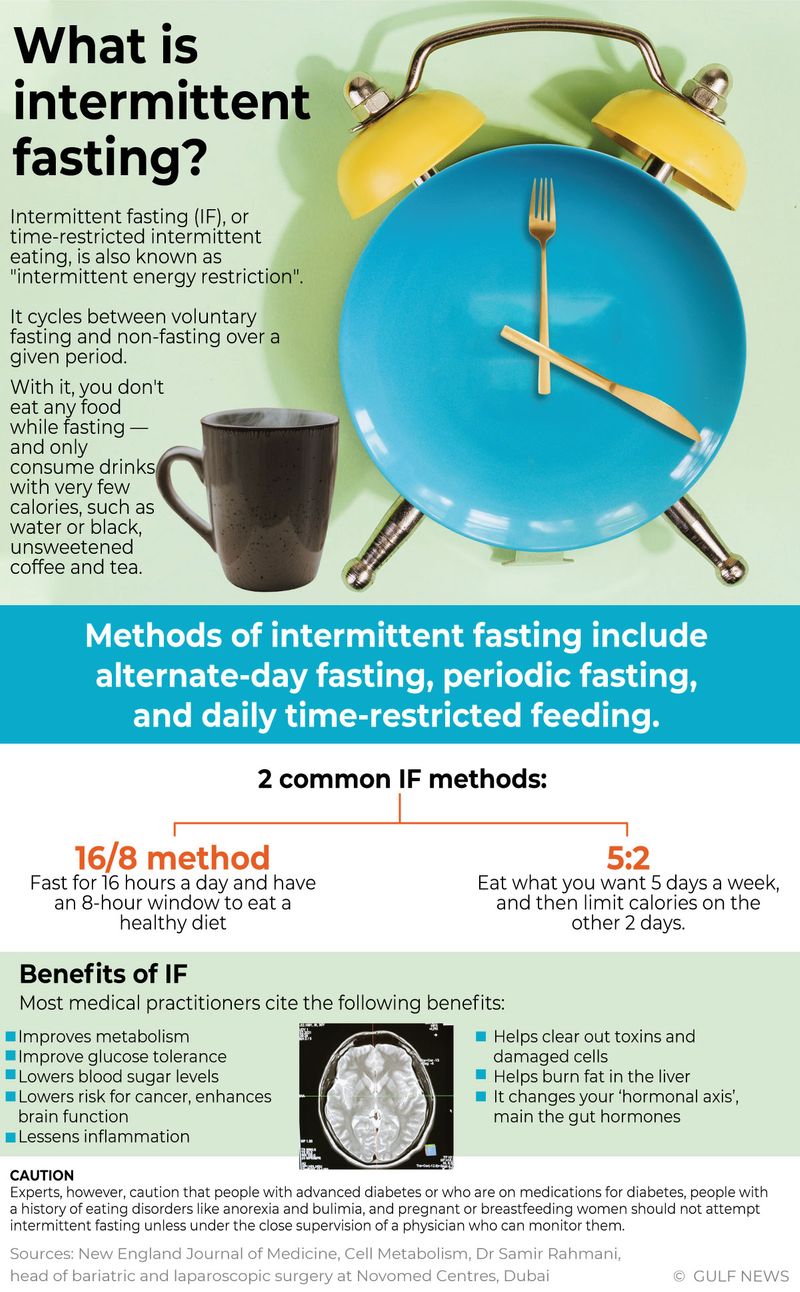

What is intermittent fasting (IF)?

It is a diet regimen that alternates between times of fasting — with no food or severe calorie reduction — and periods of eating. Evidence shows those who observe IF alongside curbing carbohydrate consumption with professional medical supervision get improved health “biomarkers”, such as blood pressure and cholesterol levels and weight loss.

What other studies show the benefits of fasting?

There are at least 40 different scientific investigations on the benefits of IF. In 2018, a team led by Roy Taylor, Ahmad Al-Mrabeh and Sviatlana Zhyzhneuskaya published in Cell Metabolism their research showing how remission in human Type 2 diabetes requires a decrease in liver and pancreas fat content.

Image Credit:

What was the profile of trial participants?

There were 72 participants — with 36 in each arm (treatment and control), between the ages 38 and 72 years.

The participants had a duration of Type 2 diabetes of 1 to 11 years, a body mass index (BMI) of 19.1 to 30.4 — 66.7% male, and had a history of use of anti-diabetic agent and/or insulin injection.

Insulin resistance

Insulin are the body’s tiny “dump trucks” specifically tasked to carry sugar in the blood into cells.

With constantly high amounts of sugar intake (esp. from carbohydrates), the pancreas needs to pump out more insulin to bring sugar in the blood into cells.

The pancreas keeps making more insulin to try to make cells respond. Eventually, the pancreas can’t keep up, and blood sugar keeps rising.

Who conducted the research?

The team was led by Xiao Yang of the Horticulture College of Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China. Other research team members include Huige Shao of the Endocrinology Department, Changsha Central Hospital, in China, and Fangzhou Bian, of the Biological Sciences, University of California Irvine, and Dr Minghai Hu, of the Department of Neurobiology and Human Anatomy, School of Basic Medical Science, Central South University, in Changsha, China.

The researchers randomly allocated the participant at a ratio of 1:1 to the Chinese Medical Nutrition Therapy (CMNT) or control group.

What was the trial outcome?

The primary outcome was diabetes “remission” — defined as a stable glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of less than 48 mmol/mol (

The secondary outcomes included HbA1c level, fasting blood glucose level, blood pressure, weight, quality of life, and medication costs.

On completing the 3-month intervention plus 3-month follow-up, 47.2% (17/36) of participants achieved diabetes remission in the CMNT group, whereas only 2.8% (1/36) of individuals achieved remission in the control group. This is equivalent to an odds ratio of 31.32.

Moreover, the mean body weight of participants in the CMNT group was reduced by 5.93 kg — compared to 0.27 kg in the control group.

After the 12-month follow-up, 44.4% (16/36) of the participants achieved sustained remission, with an HbA1c level of 6.33% (SD 0.87).

The medication costs of the CMNT group were 77.22% lower than those of the control group (60.4/month vs 265.1/month).

What is CMNT>

In general, Chinese medicine recognises that food is medicinal therapy. Chinese Medical Nutritional Therapy (CMNT) uses the principles of Chinese medical theory and modern nutrition.

It evaluates individual foods by the way they affect the body, and believes that food can either support healthy function in the body or add to its dysfunction.

What do other studies show in terms of the benefits of IF?

A Harvard team medical review of 40 studies found that intermittent fasting was effective for weight loss — with a typical loss of 7-11 pounds over 10 weeks.

The review, however, pointed out that those 40 or so studies had so “much variability” — ranging in size from 4 to 334 subjects, and followed from 2 to 104 weeks.

The review, however, outlined several key points on IF:

- Until the JCEM human trial on IF among diabetics came out, calorie restriction has already shown in animals to increase lifespan and improve tolerance to various metabolic stresses in the body.

- The evidence for caloric restriction in animal studies is strong, the recent clinical study is less convincing due to the small number of trial participants.

- Proponents of IF believe the positive stress created of intermittent fasting causes an immune response that repairs cells and produces positive metabolic changes (reduction in triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, weight, fat mass, blood glucose).

- Certain persons who eat only one or two meals each day or do not eat for long periods of time may be more compliant with this type of regimen.

- Persons who eat or snack excessively at night may benefit from a “curfew”.

What are the potential downsides of IF?

- In general, going into IF is best done under the guidance of a physician (which may entail effort/cost).

- IF may be difficult for someone who eats every few hours — e.g., snacks between meals.

- It would also not be appropriate for those with conditions that require food at regular intervals due to metabolic changes caused by their medications.

- > Prolonged periods of food deprivation or semi-starvation places one at risk of “rebound” — overeating when food is reintroduced — or an increased fixation on food.

Who should abstain from IF?

Individuals with the following conditions should abstain from intermittent fasting:

- Eating disorders that involve unhealthy self-restriction (anorexia or bulimia nervosa)

- Use of medications that require food intake

- Active growth stage, such as in adolescents

- Pregnancy, breastfeeding

Traditionally, fasting is a universal ritual used for health or spiritual benefit, described in a number of religious texts. In addition, the works by Socrates and Plato also describe some benefits from the practice of fasting.

“Beego”, a traditional Chinese water-only fasting practice initially developed for spiritual purposes, later extended to physical fitness purposes.

What can be done further to prove/disprove study’s findings?

The researchers recommend more high-quality studies involving a higher number of volunteers in randomised controlled trials, including a follow-up spanning more than a year.

How fasting triggers death in old cells in the body

Compared with newer cells, aged cells tend to be packed with toxins. Toxins are a by-product of cell metabolism (chemical changes that take place in a cell).

In general, each cell takes the benefit from the energy supplied — such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a substance found in cells that provides energy for metabolic processes.

Within cells, chemical changes take place. Energy and basic components are provided for essential processes, including the synthesis of new molecules and the breakdown and removal of others.

Just as our body absorbs the nutrients after meals, there will be by-products, which the body must push out through excretion: cell metabolism follows a similar pattern.

The by-product of this metabolic process carry toxins. Over time, a cell will have lots of toxins that need to be expelled. However, the body can’t expel it under normal circumstances.

But fasting helps expel old cells in a process called “apoptosis” (literally “falling off,” as leaves from a tree).

Aged cells, as well as abnormal or bad cells, are very sensitive to a short term of fasting. They just die straight away. They lack the tolerance to resist any lack of energy.

New cells tend to survive longer.